For the first time, traditional television and newspaper outlets, long dominant in shaping election narratives, were completely outmaneuvered by online platforms and digital journalism. This article examines how every major outlet got it wrong and what this means for the future of information power in Japan.

😟 Takaichi’s Landslide Victory

The 2025 LDP leadership race was a fierce three-way contest among Sanae Takaichi, Yoshimasa Hayashi, and Shinjiro Koizumi. In the final runoff, Takaichi secured 185 votes (149 from lawmakers and 36 from local members), defeating Koizumi’s 156 votes (145 lawmakers and 11 local).

She achieved a decisive turnaround, fueled by strong grassroots support. The outcome shattered the forecasts of all major outlets—Nikkei, Yomiuri, Asahi, and NHK included—each of which had predicted a Koizumi edge. NHK and Asahi in particular reported that Takaichi would “struggle beyond the conservative base,” but reality told a different story.

🤔 Why the Media Got It Wrong

The main reason for this failure was the misreading of party member sentiment. Nikkei wrote before the vote that Koizumi was “expanding support as a reformer,” while Yomiuri called him a “symbol of generational change.” Asahi and Mainichi, from a liberal perspective, painted Takaichi as a “hardline conservative” and an “Abe loyalist.” Television stations followed the same tone. TBS and TV Asahi, while acknowledging her as the “first potential female PM,” repeatedly questioned her “aggressive” stance on security.

These narratives, however, diverged from the actual priorities of LDP members—many of whom valued economic revival and national resilience over fiscal restraint. The elite-centric analysis of Tokyo-based media failed to capture this provincial conservatism.

😠 Social Media Shifts the Battlefield

Meanwhile, online networks became the true arena of political communication. On X (formerly Twitter) and YouTube, full-length debates, press conferences, and speeches were streamed directly to the public. Voters could judge candidates’ words without editorial filters. Even when clips circulated, the original source remained easily accessible, limiting misinformation.

Platforms like Niconico streamed policy discussions in real time, making online spaces a source of primary information rather than mere commentary. This shift marked the moment when social media overtook television as the default venue for political evaluation.

😂 The Bunshun Bomb: Digital Journalism at Its Peak

During the campaign, Weekly Bunshun published a major exposé on Shinjiro Koizumi’s alleged stealth marketing ties. The story spread instantly across X, YouTube, and discussion forums, damaging his image and arguably influencing the final momentum.

Bunshun, once a traditional print magazine, has mastered the hybrid model of investigative journalism and online virality—publishing scoops on its website first, then letting social media amplify them before other outlets follow up.

Whether one views its methods as fair or not, Bunshun’s agility exemplified a new media cycle led by the Internet rather than by TV editors.

🤩 The Day the Internet Surpassed TV

This election echoes a broader trend in Japan’s media landscape. In the 2024 Tokyo governor race, Shinji Ishimaru reached young voters directly through social media, outperforming every TV poll forecast. In Hyogo’s gubernatorial election, Motohiko Saito leveraged local online communities for re-election.

Even in the 2025 Tokyo assembly and general elections, outcomes diverged sharply from network projections. Digital sentiment now rivals traditional polls in shaping voter behavior. While old and new media coexist for now, their influence is increasingly balanced—and the momentum is with the digital side.

😫 The Limits of Television Journalism

Most Japanese broadcasters remain constrained by sponsor expectations and urban liberal audiences. Programs like TBS’ Hōdō Tokushū and TV Asahi’s Hōdō Station framed Koizumi as a “youthful reformer” while labeling Takaichi as a “conservative hawk.” Even NHK’s supposedly neutral analysis portrayed her defense and diplomacy views as alarming.

These editorial biases sparked immediate backlash online. Comments such as “TV can’t be trusted anymore” and “the Internet is faster and clearer” trended for hours. To survive, broadcasters will need to rebuild trust through neutrality, transparency, and real investigative work—the kind Bunshun has already adapted to digital distribution.

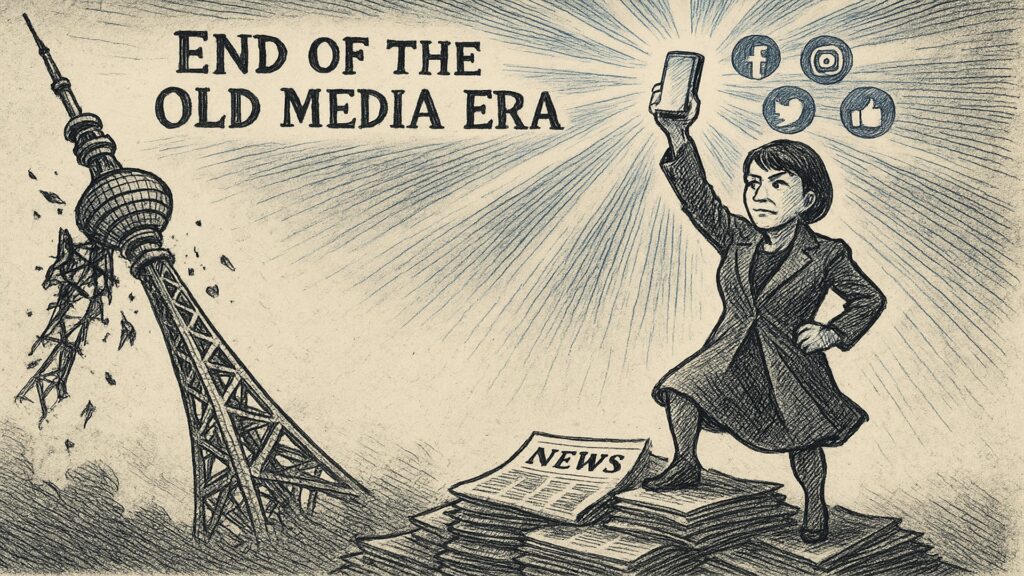

😵 Conclusion: End of the Old Media Era

Takaichi’s victory represents both a political milestone and a symbolic transfer of informational power. The age when TV and newspapers could define public sentiment alone is ending. In this election, traditional outlets misread both the mood and the mechanics of party voting, while online users accessed unfiltered footage and formed independent judgments.

For legacy media to regain credibility, they must embrace transparency and restore balance in political coverage. Otherwise, they risk being relegated to secondhand interpreters of stories already broken online. The rise of Sanae Takaichi thus marks not just Japan’s first female premiership—but the dawn of a new media order.