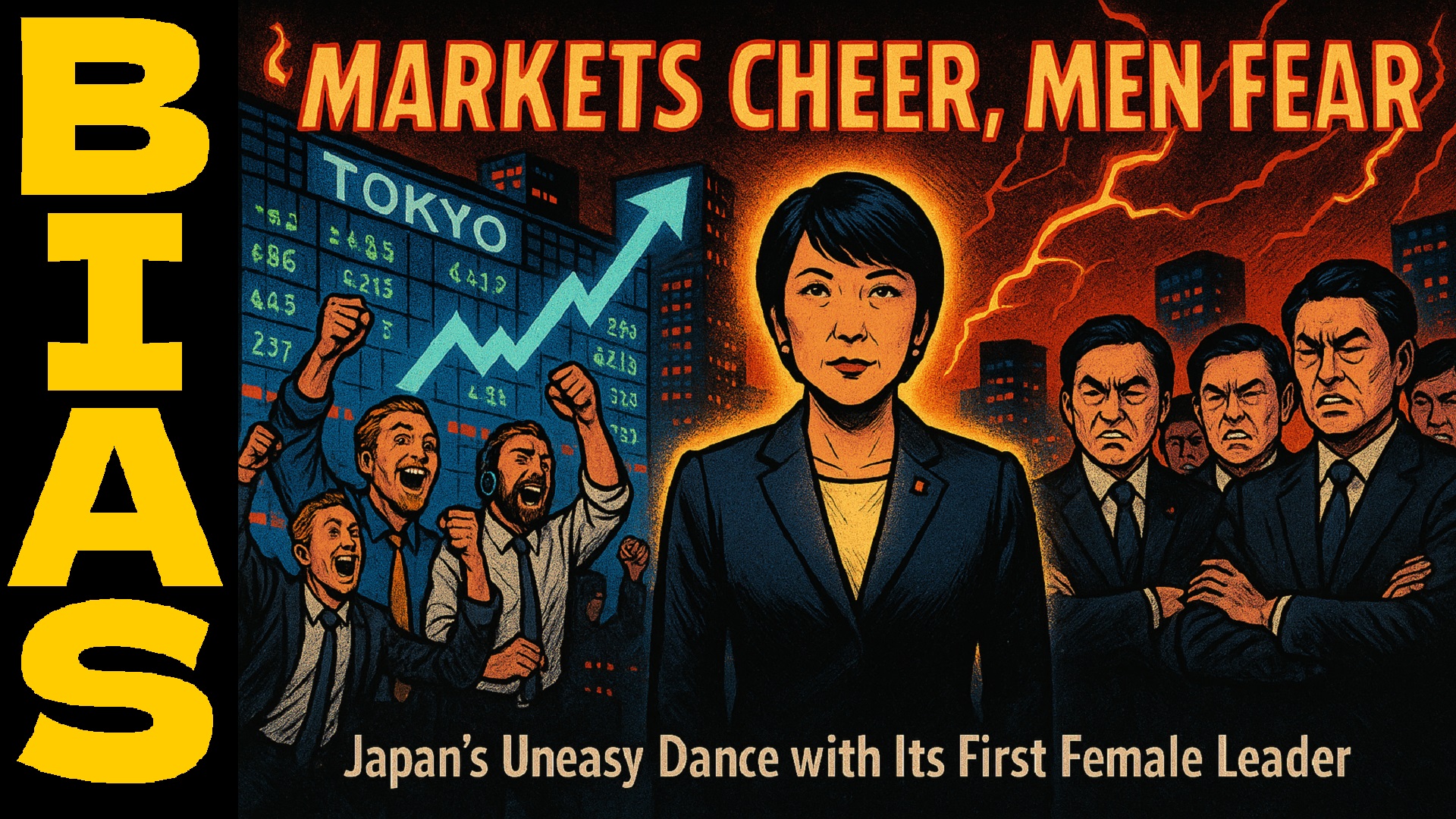

When Sanae Takaichi became the leader of Japan’s ruling Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) in October 2025, global media called it a revolution: Japan’s first woman to stand on top of its political pyramid. Yet the domestic press had other plans. Headlines focused on her loyalty to Shinzo Abe, her temperament, or even her hairstyle—less about her economic policies and more about her “tone.” The contrast revealed a deeper truth: in Japan, the media doesn’t just report power—it protects it.

🤔The Framing Game

Coverage during the leadership race showed how framing defines perception. Takaichi was called “hardline,” “emotional,” or “too strong.” In Japanese media, these words often substitute for “unfeminine.” Policy questions about defense, inflation, or foreign relations took a backseat to lifestyle details. When men are assertive, they’re “decisive.” When women are assertive, they’re “abrasive.” It’s an old playbook still alive in the newsrooms of Tokyo.

📺Symbolism over Substance

After a brief celebration, skepticism took center stage. Talk shows filled with male pundits debated whether a woman could “unite the party” or “command respect abroad.” News anchors wondered if she could “handle pressure.” But none asked whether Japan’s media could handle a female prime minister. Structural issues like the gender wage gap, political harassment, and work–life policy were left unspoken. Takaichi became both subject and symbol—a mirror reflecting a society uncomfortable with women in control.

🎥Behind the Cameras

The imbalance isn’t just on-screen. A 2024 survey by the Japan Federation of Press Workers’ Unions found that less than 15 percent of editorial managers are women. Male anchors dominate prime-time political programs, deciding which stories matter. When female politicians face harassment, reports soften the language—“verbal exchanges,” “misunderstandings.” The press, consciously or not, shields male behavior from scrutiny and treats sexism as an editorial footnote.

👓The Paternal Lens

Interviews with female lawmakers expose a quiet pattern: reporters asking about family life, fashion, or “intuition.” Such questions aren’t harmless—they reinforce the belief that women in politics are guests in a male domain. Female journalists who challenge this culture often face the same patronizing tone inside their own organizations. Journalism becomes a reflection of the power structure it claims to investigate.

🌍International Contrast

Elsewhere, media reforms have rebalanced the narrative. In New Zealand and the Nordic countries, women hold around 40 percent of newsroom leadership roles. Studies show this diversity shifts coverage toward substance: policy over personality. Japan’s ratio remains below 15 percent, ensuring that the “old boys” still control the camera angles. The difference isn’t only cultural—it’s structural.

🔄The Feedback Loop

Media bias shapes public expectation. Viewers internalize gendered cues—men as rational, women as emotional—and carry them to the ballot box. Politicians adapt, toning down assertiveness to avoid being labeled “shrill.” Thus, the press not only mirrors inequality but multiplies it. Japan’s democracy ends up echoing its own prejudices back through every screen.

😐Reflection

Takaichi’s rise revealed two ceilings: the glass one of politics and the mirrored one of media. As long as political journalism remains dominated by men, every woman who gains power will be framed as an exception, not a precedent. If Japan wants a modern democracy, it must reform not just who leads—but who tells the story. Until then, even its first female prime minister will remain a supporting character in the narrative written by the old boys behind the cameras.